On January 21, 2020, officials from CDC announced the first case of COVID-19 in the U.S., starting a two-and-half-year public health national emergency that would see nearly 6.5 million officially dead (worldwide) from the disease and likely four times that killed unofficially.

On May 18, 2022, the U.S. Department of Health and Human services announced the first case of monkeypox, now grown to over 16,000 worldwide of which 2,000 are in the U.S.

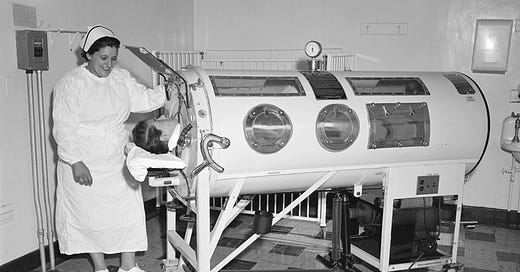

Then, on July 21st, health officials announced the occurrence of the first case of polio in the United States since 2013.

At any other time, a polio case in a country that has eliminated the disease from its shores would have been a crisis. But disease crises now seem to come faster and more furiously. In Summer 2022, government officials are focused on economic woes, war in Ukraine and supply chain crises. Health officials around the world also have their attention elsewhere, either struggling to keep emergency rooms functioning in the midst of yet another COVID-19 wave or still struggling to get vaccination programs for COVID-19 working.

So in that context, is one case of polio in the U.S. really cause for alarm? In a word, yes. More importantly, the reasons for this should be sounding massive alarm bells for monkeypox, COVID-19 and whatever the next Outbreak Disease X is.

In fact, the international spread of polio is already deemed a public health emergency of international concern by the WHO’s International Health Regulations Emergency Committee. This emergency was declared by the WHO Director General in May 2014 and the Emergency Committee has most recently focused on worries about wild polio outbreaks in several countries.

But the lessons that this polio case can teach us about monkeypox and COVID-19 are multiple. Firstly, it is not about this one polio case. The bottom-line issue is the lurking presence of a crippling disease that we have conveniently forgotten about in high-income countries.

Secondly, we need look no farther than some of the recommendations from the Polio Emergency Committee for lessons that apply to other outbreaks, especially our next phase with COVID-19.

High-risk, frequently mobile, populations are the spark for disease outbreaks – Populations without access to health services, living in economically precarious situations have been the source of outbreaks from Ebola to yellow fever to cholera over decades. In this age, migrants, refugees, and other displaced populations represent specific risks of international spread.

Conflict has exacerbated issues on outbreak response for all three diseases – In WHO’s 2019 report on progress on achieving the health goals as part of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, the areas of the world that are farthest behind on universal health coverage (UHC) and other goals (and falling farther behind) are countries in conflict. Outbreaks of highly transmissible diseases feed of off such contexts.

Poor immunization coverage is the fuel that keeps outbreaks going – Clearly, gaps in polio immunization have led to local outbreaks and an inability to declare polio eradicated and now has allowed an unvaccinated individual to bring polio to the U.S. Low COVID-19 immunization coverage in many countries has allowed successive waves of cases to be bigger and more severe. Finally, the literal fact that we no longer immunize for smallpox has left millions around the world vulnerable for monkeypox.

Inadequate surveillance is the first result of the complacency that inevitably arises from long-lasting outbreaks. We have certainly seen this with COVID-19 as testing rates have fallen dramatically around the world over the past weeks. However, we have also seen this problem in many parts of the world where access to genetic sequencing and strong laboratory networks keep many low- and middle-income countries in the dark when it comes to outbreaks.

High numbers of “zero vaccination dose” children around the world show systematic weaknesses in health systems. We have fewer immunized children now than at any time in the past three decades and more children who have had “zero” doses of any immunization. WHO and UNICEF have recently come out with their 2022 report on childhood immunization levels. Their report concludes that 25 million children have missed immunization during the pandemic, leaving entire communities open to huge outbreaks of measles and other deadly diseases. Those zero-dose children are part of “zero-service” families who have little to no access to any key health service. Low immunization coverage shows where are health systems are weakest and will be at the heart of future outbreaks.

All of these factors will contribute to a wider set of outbreaks of polio in the coming months. They have already contributed to the uncontrolled spread of monkeypox. And of course, these factors are at the heart of why the COVID-19 pandemic remains in uncontrolled spread around the world, even with tens of millions of young people set to return to school in the northern hemisphere in a month and a fall/winter surge of cases to come on top of already astronomical case levels.

On the other hand, this list also gives us a basic roadmap of “opportunities” for preparing for the next public health emergency of international concern.

If there is one bright spot in this otherwise shocking appearance of polio, it is this: that by recognizing what polio experts have been telling us for years about that outbreak, we could possibly find ways of addressing all outbreaks.